A growing number of households across Montana are struggling to afford safe and stable housing. Nearly every community in Montana lacks an adequate supply of affordable rental homes, making it difficult for families to find a place to rent within their means.

Rent is generally considered affordable when housing costs are 30 percent or less of a household’s income. Yet, the majority of Montana families living in poverty spend considerably more. Montana’s housing affordability crisis has serious consequences for individual households and the communities in which they live, as well as the overall economy. Families that cannot access affordable housing are at the greatest risk of experiencing food insecurity, homelessness, and poor academic and health outcomes for children. Despite overwhelming evidence that affordable housing stabilizes low-income families and promotes thriving local economies, Montana is one of a handful of states that does not invest state resources in housing assistance. Increasing state and federal investment will reduce hardship among Montana families living in poverty and help build inclusive, prosperous, and sustainable communities that benefit all Montanans.

This report is the first in a series exploring the issue of housing security and the growing affordability crisis facing Montana. It provides an overview of rental affordability challenges for low-income households and the central role housing plays in individual and community well-being and makes the case for greater public investment in housing assistance.

Housing Affordability in Montana: Where We Are Today

Affordable Housing: Housing costs, including utilities, that are 30 percent or less of a household’s income.

Cost Burden: Paying more than 30 percent of income towards housing costs, including rent and utilities

Severe Cost Burden: Paying more than 50 percent of income towards housing

Fair Market Rent (FMR): Estimated cost of rent in a region. HUD sets FMRs annually to determine levels of assistance for renters.

Housing costs represent a much larger piece of the family budget than food, transportation, and other expenses than ever before, particularly for those living in poverty. When the Official Poverty Measure (OPM) was established in 1960, the dollar amount used to determine the poverty threshold was based on food expenses because a typical family spent about one-third of its income on groceries. Living costs have changed significantly since then. Today, housing is the main driver of the family budget while groceries make up only one-seventh of a typical family’s expenses.[1] However, the poverty threshold remains tied to food costs and, therefore, does not accurately measure the amount of money a family actually needs to afford housing, food, and other basic necessities. If the official poverty measurement was adjusted to reflect the cost of housing, in addition to child care and health care, the number of people living in poverty would be significantly higher.

Montana’s housing prices have increased significantly over the past several decades, while incomes have not kept up the pace. Since 1990, median gross rent grew by 26 percent, compared to the national rate of 16 percent, ranking rent costs in Montana the 11th fastest growing in the country.[2] Median incomes only increased by 21 percent over the same period. Low-income Montanans now spend ten percentage points more of their income on housing compared to what they spent two decades ago.[3] While many communities have experienced a surge in housing costs, prices have sky-rocketed in Montana’s fastest growing cities. This is most notable in Bozeman and Gallatin County where, over the past six years, the cost of housing has risen by more than 50 percent.[4]

When real estate becomes more expensive and demand grows, those with the lowest incomes face the greatest shortage of affordable rental housing. Elderly and extremely low-income renters are the most affected by housing challenges in Montana than any other household type.[5] There are only 52 affordable homes for every 100 extremely low-income renters according to an analysis by the National Low-Income Housing Coalition. Montana would need to see an additional 16,467 housing units to make up for this shortfall.[6]

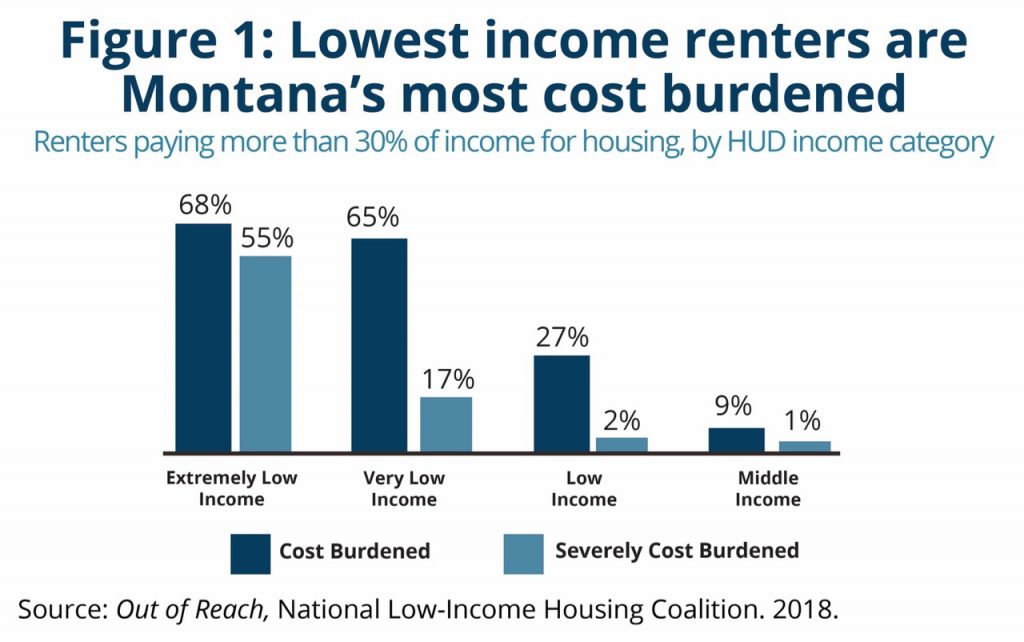

In Montana, 39 percent of all renters are cost burdened.[7] One in four renters are considered extremely low-income and, of these households, 68 percent are paying rents that are unaffordable (see Figure 1).[8] The majority of extremely low-income renters are seniors or people with disabilities (57 percent) or are working (36 percent).[9]

The gap between wages and housing costs makes finding an affordable home increasingly out of reach for workers, and a full-time job does not ensure access to safe and stable housing. One in four jobs in Montana are in low pay occupations, with annual earnings below the poverty line for a family of four ($24,300).[10] Workers without affordable housing make up a large share of the low wage workforce, with more than a third of extremely low-income renters employed in the service industry, which includes retail workers, home health aides, and those working in food services.[11]

Despite seeing the fourth fastest wage growth in the last decade, wages in Montana remain very low compared to the national average, ranking 45th lowest of all the states.[12] Although Montana’s economic growth today is driven by the service industry -- with retail, accommodation, and food services projected to add over 1,000 new jobs per year and over $70 million to GDP -- earnings for these jobs remain skewed towards low and minimum wage.[13] As a result, many working Montanans pay larger shares of their income towards rent.

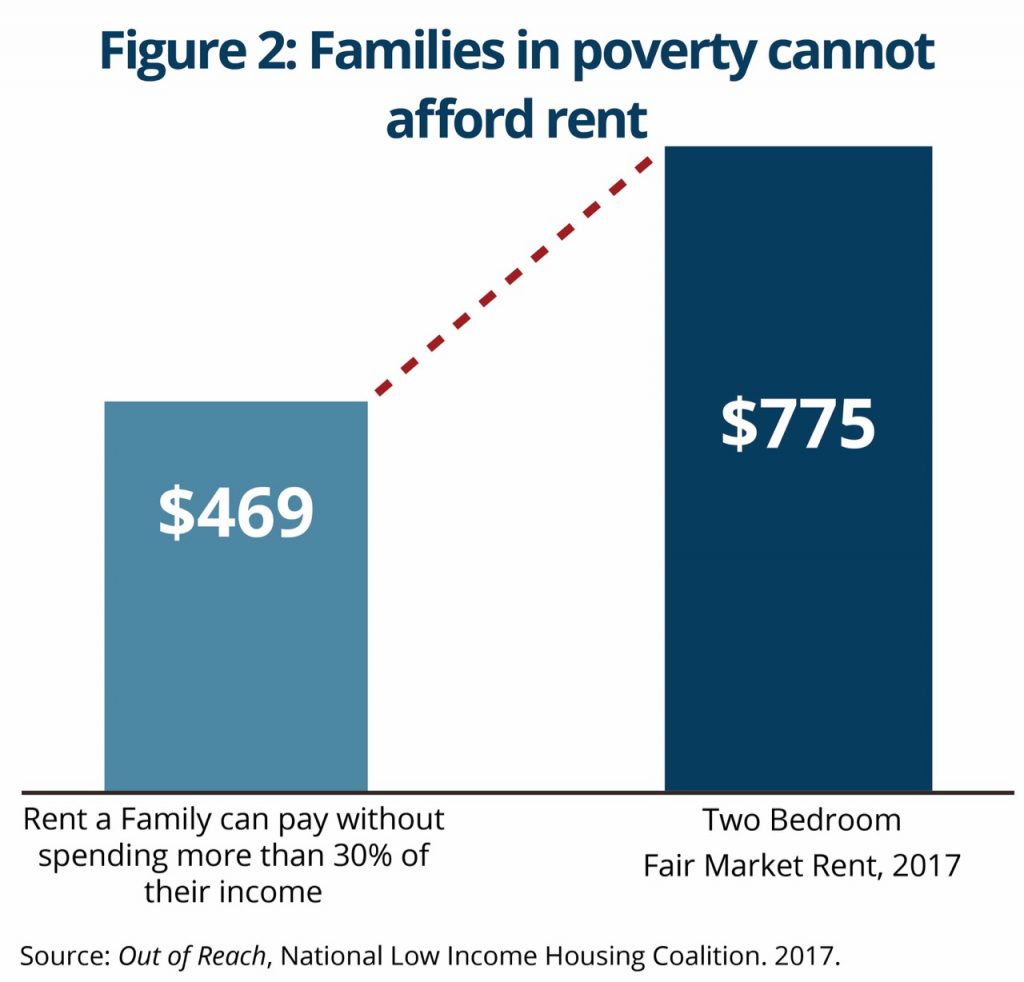

A family living in poverty should pay no more than $469 for housing to be affordable (see Figure 2). In 2017, the fair market rent in Montana for a two-bedroom home was $775 a month.[14] In order to afford this, a worker would need to earn $14.90 per hour. A single working mother earning minimum wage ($8.15/hr) would need to work 73 hours a week to afford a two-bedroom apartment.

Seniors and those with disabilities who live on a fixed income face an even greater burden. An individual relying on Social Security can afford to pay no more than $221 a month for their housing.[15] Affordability challenges are projected to worsen for the aging population, given that those aged 55 and older make up Montana’s fastest growing population.

Rental Assistance Provides Critical, but Inadequate, Support

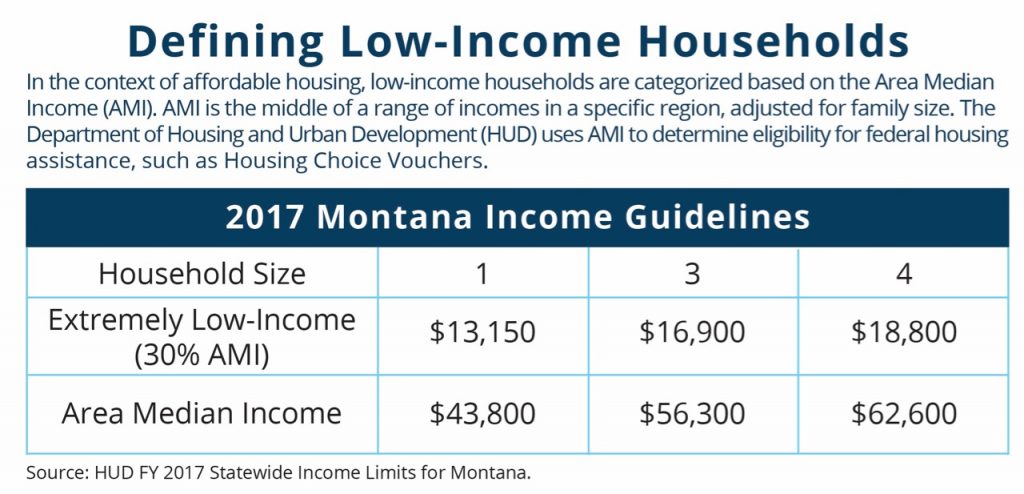

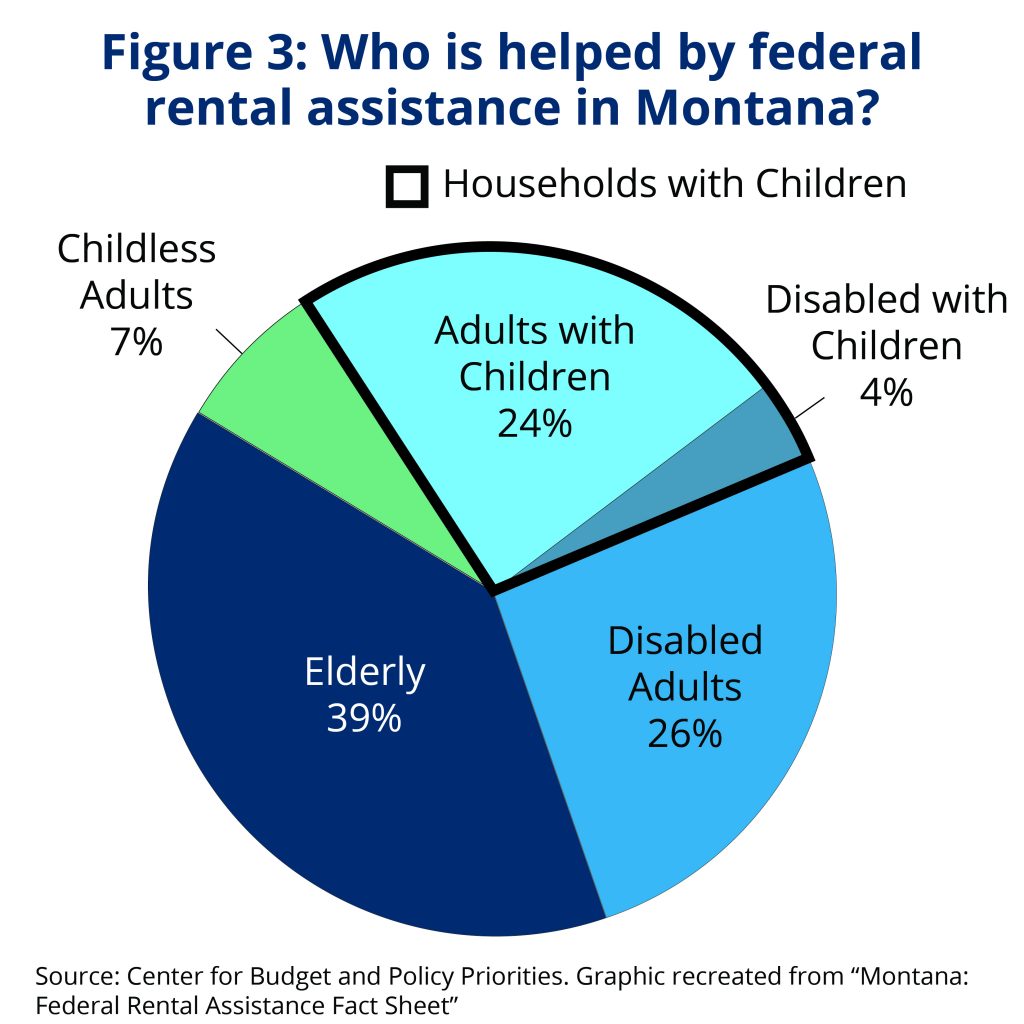

Across Montana, 14,000 households use federal housing assistance to keep a roof over their heads and nearly all (93 percent) assisted households include families with children and people who are disabled.[16] Housing Choice Vouchers (HCV) are the largest source of federal housing support, a program that allows families to spend 30 percent of their income on rent with HCV paying the difference.[17] The amount of federal resources, however, does not come close to meeting Montana’s housing needs and most low-income, cost burdened renters do not receive assistance. Today, 29,000 low-income households, the majority of whom live below the poverty level, spend more than half of their income on rent.[18] This represents a 30 percent increase compared to a decade ago. Of those receiving assistance, the vast majority are families with children or are seniors or individuals with disabilities (see Figure 3). Federal guidelines require that at least 75 percent of households admitted to the voucher program are extremely low-income (in Montana, about $16,900 for a family of three).[19], [20] However, the vast majority of Montana voucher holders have considerably lower incomes, earning an average of $11,700 a year.[21]

The amount of federal resources does not come close to meeting housing needs. There are roughly 3,340 renters supported by housing choice vouchers in counties across Montana, with twice as many applicants (6,762) on waiting lists.[22] Unlike other critical safety net programs, like Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), that adapt according to community and family needs, rental assistance is not an entitlement and these benefits are not provided to all those who qualify. Public housing authorities contend with growing numbers of applicants for housing support while levels of federal funding steadily decline. The federal government spent $2.9 billion less on housing assistance in 2015 than it did in 2004.[23] Over this period, the share of housing vouchers going to Montana families fell 20 percent, a shift that reflects more seniors and adults with disabilities using assistance and a larger share of vouchers targeted towards homeless populations.[24]

Local communities have felt the impacts of decades of federal disinvestment. For example, in 2008, the Helena Housing Authority received $600,000 to distribute in rental assistance. By 2016, it had lost $170,000 in federal dollars.[25] Meanwhile, over 600 families in Helena sit on a waitlist for assistance.[26] The unmet need for housing vouchers is most severe in Great Falls, where more than 1,330 families wait for a voucher to become available. Depending on the county and level of demand, an applicant can wait between 18 months to seven years to receive assistance.[27]

Rental Assistance Supports Family Security and Healthy Children

A stable and affordable home is the foundation of a family’s health and financial security and a child’s academic and future success. For households burdened by unaffordable rent costs, there is little left over to pay for food, transportation, and health care. Many families find themselves one financial setback from losing their homes. Housing assistance can help cost burdened families at risk for housing instability and homelessness achieve long-term stability, improve a child’s educational and adult outcomes, and significantly reduce poverty rates for families and their children.

Financially Secure and Healthy Families

Rental support plays a critical role in the fight against poverty, lifting four million people above the poverty line in 2015.[28] Limiting housing costs allows low-income families to direct more of their resources towards better food, education, and savings which directly improves quality of life and financial security. The impact of housing benefits is so substantial that increasing assistance to a targeted group of 2.6 million rent burdened families could decrease child poverty by as much as 21 percent.[29]

When rent consumes most of the household budget, families are left with very little to get by. According to an analysis by the Federal Reserve, severely cost burdened, low-income renters with children have just under $450 dollars in remaining income after paying the rent.[30] Devoting large shares of income to housing forces families to make difficult tradeoffs to make ends meet, spending just under $300 per month (or about $10 per day) on food, and 75 percent less— just $18 per month—on health care than those without cost burden.[31]

Conversely, families living in affordable housing are able to dedicate nearly five times as much to health care, a third more to food, and twice as much to retirement savings compared to those who are rent burdened.[32] Children in subsidized housing are more likely to meet “well-child” criteria, such as better access to nutritious food and lower rates of food insecurity, than children on waitlists for housing assistance.[33] Furthermore, housing assistance is linked to improved parenting behaviors and bonding with children, in part because parents reported feeling less stress when rent was affordable.[34]

Housing Stability and Education

Without a stable and affordable place to live, many families are forced to move homes frequently, often more than once or twice a year. Those who involuntarily move due to eviction or poor housing quality are likely to end up in worse housing conditions and in neighborhoods with higher poverty rates.[35] Research highlights that frequent and sudden disruptions in a child’s environment can cause toxic stress, heightening risk for cognitive impairment and stress-related disease.[36]

Residential instability, particularly in the early years, is among the strongest predictors of lower school performance. Young children from low-income families that experience more than three moves in their first five years do worse than their peers on school readiness measures, like attention and healthy social behavior.[37] For every residential move before second grade, a child’s math and reading scores are shown to drop relative to peers, an achievement gap that is not made up throughout elementary and middle school.[38] Frequent moves can result in switching schools more often, which increases the chances a student will leave school altogether. Low-income students who experience multiple school changes during the K-12 years are less likely to finish school on time and complete fewer years of school.[39] A child who moves three or more times before the age of seven is 19 percent less likely to graduate from high school.[40]

Housing choice vouchers can affect a child’s educational outcomes by decreasing the likelihood that families make disruptive moves and give families greater choice in where they live. Evaluation of HUD housing assistance from 2000 to 2004 found that having a voucher reduced the number of residential moves by nearly one move, compared to two moves for families without assistance, and voucher holding families were more likely to settle in lower poverty neighborhoods.[41] A large body of evidence demonstrates that better access to quality schools and community resources helps close the achievement gap for children living in poverty. Research in Montgomery County, Maryland found that elementary school students in subsidized housing who live in low poverty neighborhoods and attended neighborhood schools made significant gains in academic performance. The research showed them closing the achievement gap with moderate-income students by half in math and by one-third in reading over just seven years.[42]

Housing vouchers that enable families to settle in higher opportunity neighborhoods help children fare better later in life. Results from HUD’s Moving to Opportunity program, which randomly provided vouchers to families living in high poverty areas, found that younger children who relocated to lower poverty neighborhoods using a voucher will have an adult annual income 31 percent higher compared to unassisted peers, lifting their total lifetime earnings by $302,000.[43] The study also found that children in families who received housing assistance were 32 percent more likely to attend college and less likely to remain in low poverty neighborhoods as adults, leading researchers to conclude that vouchers may reduce the intergenerational persistence of poverty.[44] A separate study examining teenagers found that each additional year a teen lived in voucher assisted housing generated a $250 to $480 annual increase in their adult income, as well as lower rates of incarceration than their unassisted peers.[45]

Reduced Homelessness and Costs to Emergency Services

For some of the most at-risk families, severe housing cost burdens can lead to losing their home entirely. High housing costs and a tightening housing market have become a leading cause of homelessness for families in poverty, and this trend is reflected in Montana’s own homeless population.[46],[47] At the time of HUD’s point-in-time survey in January of 2017, 987 individuals were unsheltered, representing a 33 percent increase since 2007.[48] More than a third of homeless Montanans are families with children, a rate considerably higher than the national rate of just under ten percent.[49] Montana schools see continued growth in numbers of homeless children, reporting that 3,000 students lacked a home of their own at some point during the 2015-2016 school year.[50]

Homelessness takes a severe toll on the health of families and poses huge costs to society. While it is difficult to measure the total financial impact of homelessness, the comprehensive No Longer Homeless in Montana survey estimates that publicly funded services, including emergency shelters, hospitals, and law enforcement, can spend upwards of $23,000 annually to care for a single chronically homeless individual.[51] More communities find that it is far less expensive to keep people housed than allowing individuals to cycle between shelters, hospitals, and other emergency facilities. Housing First programs prioritize finding and maintaining stable housing and providing long-term rent assistance. This model of addressing housing before a person’s other needs is more effective and less costly way to tackle homelessness.[52] The results from a pilot supportive housing program in Bozeman estimated that the city’s public services spend a combined $28,000 annually per chronically homeless, high-need individual.[53] Providing long-term housing assistance and health care for the same high-need individual was considerably less, at $11,800 per person. Further, this individual was also less likely to use emergency rooms as primary care or become homeless again.[54]

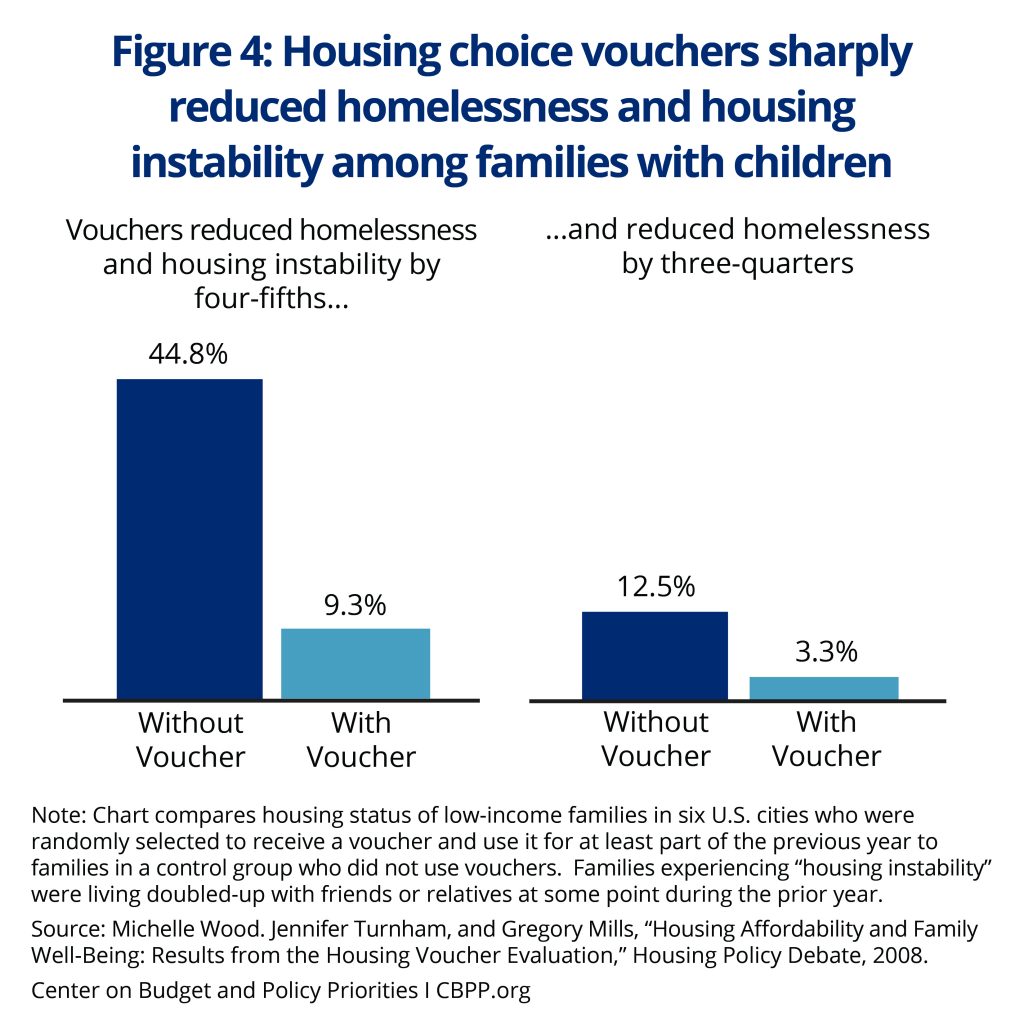

When coupled with coordinated services, housing choice vouchers are effective tools that sharply reduce homelessness and stabilize at-risk families. A multi-year evaluation of low-income families with children found that vouchers decreased the number of families living in shelters or on the streets by three-fourths and cut the number of family moves by nearly 40 percent. [55] A separate study of families living in homeless shelters showed that families who were given vouchers were half as less likely to experience another episode of homelessness and 42 percent less likely to have their children placed into foster care.[56] Furthermore, providing vouchers for these families was significantly less costly than the assistance provided through emergency shelter care and transitional housing.

Affordable Housing Strengthens Local Businesses and Our Economy

An adequate supply of affordable homes is essential for local businesses and economies to attract the workforce needed to grow. Each dollar invested in affordable housing construction and rehabilitation creates jobs, boosts local spending, and increases tax revenue that can be reinvested in schools, hospitals, and other critical institutions and services.

Helps Businesses Retain Workers and Stay Competitive

Investing federal and state dollars in constructing and maintaining low cost housing will preserve affordability for working families and allow employers to hire the workforce they need. Thousands of new low-to-middle wage jobs have increased demand for affordable housing, and the lack of housing options has become a barrier to business growth. An overwhelming number of Montanans report that employers, particularly in rural communities, have difficulty finding workers due to a lack of affordable housing.[57]

Businesses take a hit when job seekers are priced out of the local housing market. The city of Whitefish, for example, has seen market rents increase by 50 percent from 2010 to 2016, and its current rent costs are unaffordable for over 70 percent of renter households living in the area.[58] Scarce rental availability for workers has led to severe labor shortages and local businesses struggle with increasing job vacancies, with approximately 225 year-round and 140 seasonal jobs going unfilled in 2016. Nearly one in three employers in Whitefish report that they recently had an employee leave or decline a job offer because that employee found a job closer to a place they can afford to live.[59]

Bringing the cost of housing down can save local businesses money associated with high employee turnover rates. A meta-analysis on the costs of turnover across various industries demonstrated that replacing a single worker earning $30,000 or less annually can cost a business 16 percent of that employee’s salary.[60] By this estimate, a Montana business could save $4,800 by retaining one employee.

Alleviating housing cost burdens among working families can increase the money available for spending on local goods and services. Lower income families are more likely to spend their dollars in their own communities, and businesses can benefit from the increased spending by these customers. If all the unassisted cost burdened low-income households in Montana received rental assistance, disposable income would increase an estimated $2,932 per year, amounting to a total investment of $110,168,250 in the sustainability of low-income families as well as additional dollars spent in their communities.[61]

Federal Investment Boosts Economic Growth

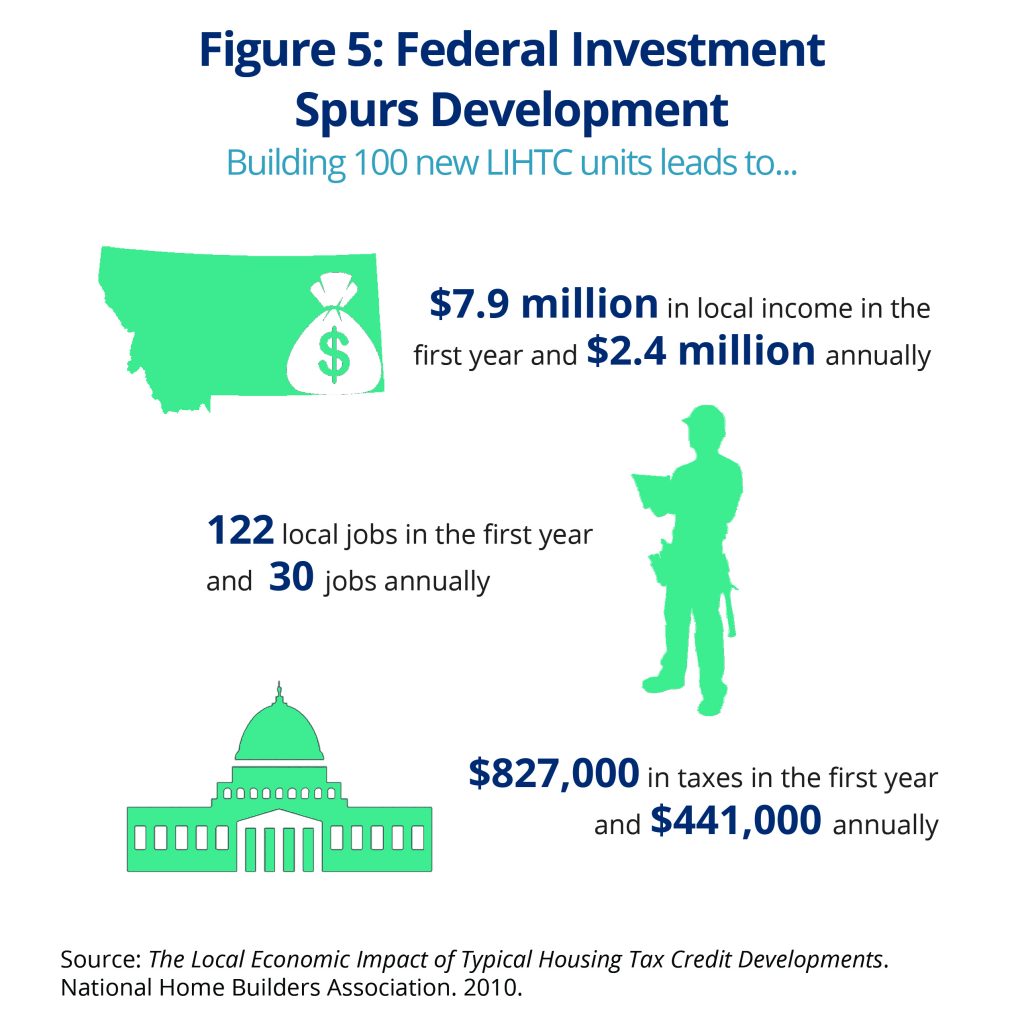

Affordable housing development and assistance brings federal dollars into communities which boosts the local economy. Federal Low-income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC), established by Congress in 1986, account for most of the housing assistance provided indirectly to low-income households. LIHTC provides federal tax credits to housing developers in exchange for building or rehabilitating rental housing that is affordable for low-income households. This program provides over $2.5 million in tax credits annually to finance the development of low-income housing in Montana communities.[62] LIHTC has had a tremendous impact in Montana. Since the program was established, LIHTC projects have financed 7,500 new homes for over 17,400 low-income families.[63] The injection of federal funds has a rippling effect in local communities. LIHTC investments have generated $808 million in local income for communities and supported 8,480 jobs since the creation of the program.[64]

For every 100 rental homes supported by low-income housing tax credits, local economies gain $7.9 million in income, $827,000 in taxes and other revenue for local governments, and 122 jobs from the construction.[65] For every dollar spent on capital and maintenance of public housing, this investment adds $2.12 of indirect and induced economic activity.[66]

In addition to federal tax credits, housing choice voucher payments can generate significant economic activity. In 2016, property owners in Montana received $30.89 million in voucher payments, which helped them pay for property taxes and prevent blight by maintaining their properties in good condition.[67]

Conclusion

State and federal investments in housing offer more than the dollar value of rent. Montana is stronger when all our residents have an affordable, safe, and stable place to call home. Affordable housing benefits individual families, the neighborhoods they live in, and our broader economy. Without state resources to expand housing affordability, more Montanans will become vulnerable to financial insecurity, poor health, and homelessness, while local economies struggle to grow. Montana should invest in the future of its children and communities by increasing the levels of assistance available and targeting its resources to meet the housing needs of its families.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.