Families Face Limited School-age Child Care Options

During the 2023 Legislative Session, Montana policymakers invested $14 million over the next two years to help make child care more affordable for families.[1] Child care is difficult for many families to find and afford across the state, including finding care for school-age children before or after school and during the summer.

Working parents often need care for their school-age children after school, before school, on weekends, over holidays, or in the summer. Care for these children occurs in a variety of settings:

The demand for afterschool programs in Montana outpaces availability in communities. More Montana students would enroll in an afterschool program if one were available to them. For every child in an afterschool program in Montana, four more children are waiting to get in.[2] More than half of parents report cost as the biggest challenge to accessing afterschool programs.[2] Parents report a lack of availability, and finding transportation to programs also presents challenges to using afterschool programs.

National estimates show that American Indian families report similar challenges to accessing out-of-school programming, including limited availability, lack of convenient locations, and high costs.[3] Additionally, American Indian families report challenges finding programs that include a cultural component, with 41 percent of parents reporting that a program their child attends does not include any cultural programming.

School-age child care programs are critical for working families who need a safe and reliable place for their older children to be while they are at work. Older children are more likely to have all parents in the workforce, with 74 percent of children age 6 and older with all parents working compared to 65 percent of children age 5 and younger.[4]

Limited Funding for School-age Programs Hurts Parents and Providers

Funding for school-age programs depends on the type of program. More than half (54 percent) of programs report receiving funding from private grants and donors in Montana.[5] Programs also use federal, state, and local funding to run programs. One specific federal grant, the 21st Century Community Learning Grant, supports out-of-school time community learning centers. In the 2020-21 school year, 29 grantees received a 21st Century Community Learning Grant, reaching 6,420 students.[6] Grant funding for school-age programs is often temporary or only a one-time opportunity and can be competitive to receive. For example, 31 applicants requested $7,540,791 in funding for a 21st Century Community Learning Grant during the 2023-2024 school year. However, only 23 grants totaling $4,222,989 were awarded, meaning only about half of the requested amount was funded.[7]

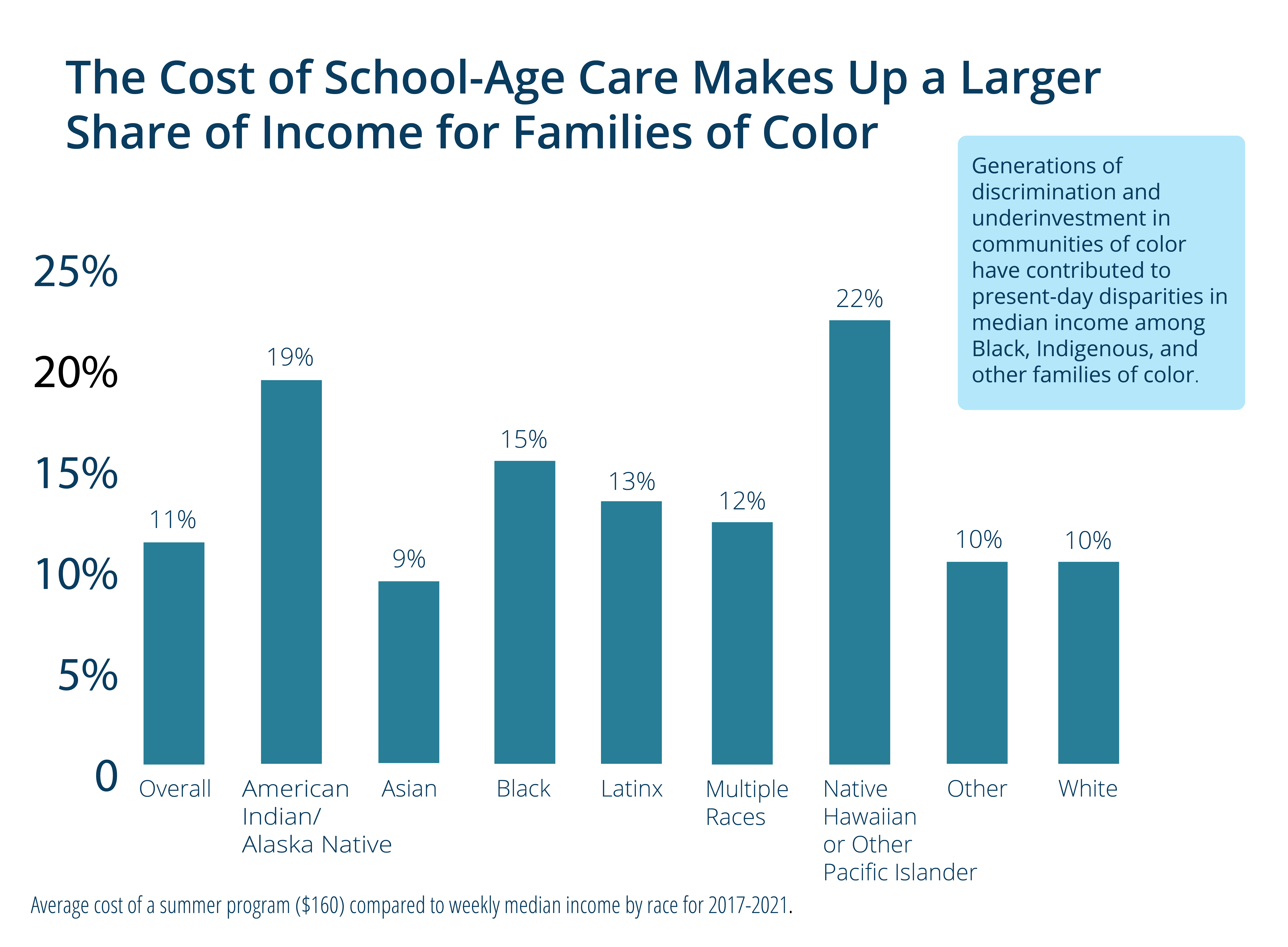

Many programs also charge parent fees to cover program costs. For example, the average cost per week for a summer program is between $160 and $170 in Montana.[2] A single parent working full time at $17 per hour spends 23 percent of their weekly income for the summer program fee for one child. Summer programs are not always full-time, leaving working parents to cover additional child care during their work hours to fill in the gaps or cut their hours to care for their older children. Nearly half (44 percent) of parents report cost as a barrier for enrolling in summer programs.

Access to affordable school-age care is a racial and economic justice issue. High costs for school-age programs puts them out of reach for many families, and they are disproportionately more unaffordable for Black, American Indian, Latinx, and other families of color due to generations of denied access to economic opportunities. The cost of a week of summer programming ($160) makes up a larger share of a family’s median income for American Indian (19 percent), Black (15 percent), Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander (22 percent), Latinx (13 percent), and multiracial families (12 percent) compared to 11 percent overall.[8] When care for children is further out of reach for families of color, it perpetuates the cycle of parents of color having limited opportunities to work or continue their education.

School-age Programs Are Currently Left Out of the Best Beginnings Scholarship

The Best Beginnings Scholarship helps families pay for child care when they are working or in school. Policymakers recently expanded eligibility for the program up to 185 percent of the federal poverty level.[1] A family of three earning less than about $45,000 a year is eligible. Children are eligible for a Best Beginnings Scholarship through age 12 and families must use a program that is licensed or registered under the state’s regulations. Current regulations do not fit school-age programs making it challenging for the few programs that do become licensed. This leaves most programs unable to accept a Best Beginnings Scholarship even if a child in attendance is eligible. For parents needing help to afford school-age care, they are left with few options to piece together care for their older children. Some families send their older children to care that’s not geared to their age, or unfortunately, older children simply stay at home unsupervised.

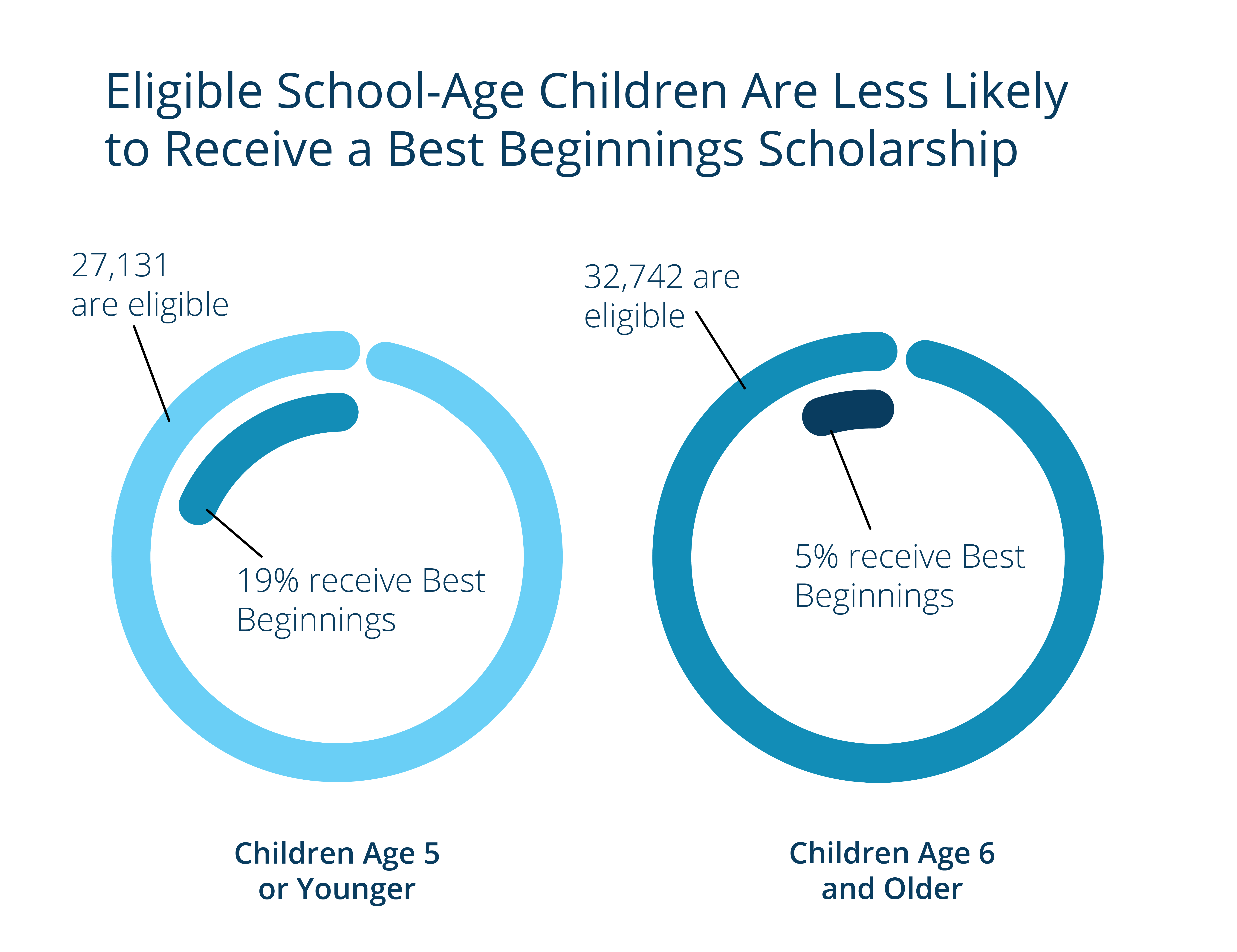

During fiscal year 2022, 6,622 children received a Best Beginnings Scholarship. School-age children (age 6 to 12) made up 23 percent of the scholarship recipients.[9] Participation in the Best Beginnings Scholarship is lower among eligible school-age children with 5 percent of those eligible participating compared to 19 percent for children age 5 or younger.[10]

During fiscal year 2022, 6,622 children received a Best Beginnings Scholarship. School-age children (age 6 to 12) made up 23 percent of the scholarship recipients.[9] Participation in the Best Beginnings Scholarship is lower among eligible school-age children with 5 percent of those eligible participating compared to 19 percent for children age 5 or younger.[10]

Creating a pathway for school-age programs to become licensed with the state expands options for eligible families with older children and helps address the cost barrier many parents face across the state. School-age licensure can also boost safety and quality in programs, providing baseline safety and training standards programs must meet. The Department of Public Health and Human Services in Montana introduced a proposal for updated child care licensing rules in November 2022 that included an out-of-school-time license category.[11] The proposal was postponed but is expected to be considered again in fall 2023.

Out-of-School-Time Programs Enrich Students’ Skills and Experiences

Creating policies that make out-of-school programs more accessible for parents means more children attend high-quality programs that benefit them in a variety of ways. For example, the majority (79 percent) of afterschool programs serve meals or snacks to students.[5] The top activities offered by 21st Century Grant programs included a focus on STEM, arts and music, literacy, and physical activity.[6] Expanding school-age care also provides an opportunity to support the state’s future workforce. Afterschool and summer programs can help students gain new skills and learn about new interests or professions.[12] Overall, out-of-school programs play an essential role for supporting children’s growth and development while also meeting the care needs for working families.

[1] O’Loughlin, H., “HB 648: Bridging the Gap to Child Care,” Montana Budget & Policy Center, Jun. 27,2023.

[2] Afterschool Alliance, “Montana after 3pm,” 2020, accessed on Aug. 17, 2023.

[3] Afterschool Alliance, “America After 3pm for Native American Families,” Jan. 2023.

[4] KIDS COUNT Data Center, “Children with all available parents in the labor force by age in Montana,” 2017-2021.

[5] Montana Afterschool Alliance, “Snapshot of Afterschool in Montana,” Oct. 2020.

[6] Resendez, M., “Nita M. Lowey 21st Century Community Learning Centers, Montana State Evaluation Report 2020-21.”

[7] Cusey, M., Montana Office of Public Instruction, “RE: 21st century grants - applicants vs. awarded,” email to Xanna Burg, Montana Budget & Policy Center, July 31, 2023, on file with author.

[8] U.S. Census Bureau, “Median Family Income in the Past 12 Months (In 2021 Inflation-Adjusted Dollars), American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B19113A-B19113I, 2017-2021.”

[9] Montana Department of Public Health and Human Services, Early Childhood and Family Support Division, special data request by Montana KIDS COUNT for State Fiscal Year 2022 data.

[10] Estimates of children eligible for a Best Beginnings Scholarship is calculated by multiplying the percent of children in families making less than 185 percent of the federal poverty level by the number of children in the matching age groups. Poverty estimates are obtained from the U.S. Census Bureau, “Age by Ratio of Income to Poverty Level in the Past 12 Months, American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates, Table B17024, 2017-2021.”

[11] Administrative Rules of Montana, Department of Public Health and Human Services, proposed changes, MAR 37-1020, Nov. 4, 2022.

[12] Afterschool Alliance, “Building Workforce Skills in Afterschool,” Nov. 2017.

MBPC is a nonprofit organization focused on providing credible and timely research and analysis on budget, tax, and economic issues that impact low- and moderate-income Montana families.